In several days, my family will mark the four-year anniversary of my dad’s death. I’ve written a lot about my dad here and elsewhere, and about the nonlinear nature of grief. That’s not what I’m going to write about today.

Like so many people, I can get stuck. I get stuck in feelings, thoughts, ruminations, even large piles of snow or sand.

In cars, in fact, I used to get stuck all the time—in the driveway, at the beach, on two tracks in the woods [don’t ask]—thinking the problem was me, my inability to un-stick myself.

Then I purchased an ancient 4x4, and realized that the problem wasn’t me; I had simply been using the wrong tools for the job.

***

I enrolled in Driver’s Ed as soon as legally possible.

I got to school hours early to watch videos about driving regulations and hazards (the “train track” VHS, the “downed powerline” VHS, the “drunk friend who wants to drive us home from the party” VHS—you may be familiar); read aloud from old DMV workbooks and, on off days, wake at 5 am to greet the instructor as he pulled up to my house for the morning driving lesson (to be held on roads empty but for the deer at dawn).

I committed to learning how to drive because I was desperate to control my own access to the wider world outside my home.

I wanted to know that if I needed to be somewhere or leave somewhere, it was in my power to do so. I saved up my waitressing cash for two summers so that I could purchase my own vehicle and hit the road whenever the spirit moved me.

But before I could do that, I practiced on my dad’s cars.

The first was an early 1980s station wagon, wood-paneled and with room enough for nine (the last couple in the back seats facing out the hatch). Yes, that car—I know you know.

The thing was huge, and heavy, and front-wheel drive. Where I’m from, lake effect snow means that every road is coated in powder and glare ice by Christmas. These are not ideal conditions in which a new driver takes to her freedom via a front-wheel drive hunk-o-steel with bald tires.

***

I led my friends in reciting the Lord’s Prayer as we careened off of Homestead Hill toward Viola’s house one fateful snowy night, en route to our high school’s February dance, a school-sanctioned “rave” put on by the student council. We did not catapult off the hill into the ditch, and still I’m not sure why not, excepting petitioning the divine in unison.

Shortly thereafter I slid in the same huge station wagon down the same steep hill on my way to school. Directly behind me, an entire yellow bus full of kids slowly reversed so that my car would not slam backward into them, forcing us both off the road.

***

The summer before I turned 17 I saw an ad for an old Subaru. $1,000 and “Rusty” would be mine. I forked over the cash, and thus commenced my four-wheel-drive conversion experience.

That winter was a hard one—record snowfall due to El Niño, and I had signed up to take community college courses during my high school afternoons, as in doing so, the school board would foot the bill and I wouldn’t have to re-take those courses the next year, in university. I’d get out of half a day of high school and save money and time! It was a win-win.

But community college was nearly an hour’s drive away, and I had to do the two-hour driving gig several times a week. The last couple of years learning to drive in my dad’s vehicles in the winter had scared me straight.

What I found, however, was that driving through blizzards and over snowy roads was appreciably different with good snow tires and four wheel drive—even if the car was a rust bucket—than in a bald-tired, two-wheel drive contraption. Knowing I had the tools to match the job made all the difference, and I drove through that year of long pursuits without getting stuck once.

There’s a lesson in that, for those of us who get stuck in the weeds of our own ruminations.

It’s easy to wonder, when a hard thing happens, or someone we love leaves this earth, why we bother to go on ourselves. There’s little logic to it, especially when the road ahead seems rife with hidden peril, and then, simply, what—just ends?

[or is that a portal?]

***

Before I drove my first 4x4 I assumed that the problems I encountered on the road had more to do with my capacity to handle them than with my mode of transport.

In that frame of mind, even the hint of snow in the air on an otherwise dry day evoked fear. Easier to stay put than to venture out, if venturing out means nothing but whiteouts and black ice.

But with repeated use of the right tools—a vehicle made to fit the conditions, say—the initial impulse to run and hide began to fade. I felt more confident, more competent. I began to understand that the journey itself may not necessarily be fraught; it may be wonderfully boring, and I may just end up at my destination in one piece. Whole.

Life itself—each day, in fact—can be wonderfully boring.

We can wake up, do the things, think the thoughts, and still make it to the end of the day whole. Loved, even. Sometimes, even happy, or joyful, possibly warmly contented. We are not broken.

Sometimes, old problems just need new tools. I forget this many mornings. I’ve re-learned it by nightfall.

***

In one excursion—after I burned out the aforementioned station wagon’s transmission upon getting stuck in the mud (literally—and this is when I learned the “rock and wait” method of getting unstuck [also metaphorically applicable!]) but before purchasing my own wheels—I made a bad call on a left hand turn into the grocery store, and collided head-on with a Dodge Ram truck. I was 16. In that moment, just as they say, time seemed to stop.

I observed, trance-like, as the huge front end of the Ram literally rammed into the front end of my dad’s minivan. I saw the glass slowly puncture and separate.

Shard by shard, frame by frame, I watched numbly while the entire windshield unfurled as if choreographed; a fissured ballet. And then: nothing.

I tumbled from the car, dazed. An older woman ran from the truck and approached me. She did not yell. She opened her arms. “You are forgiven” she said, and held me.

***

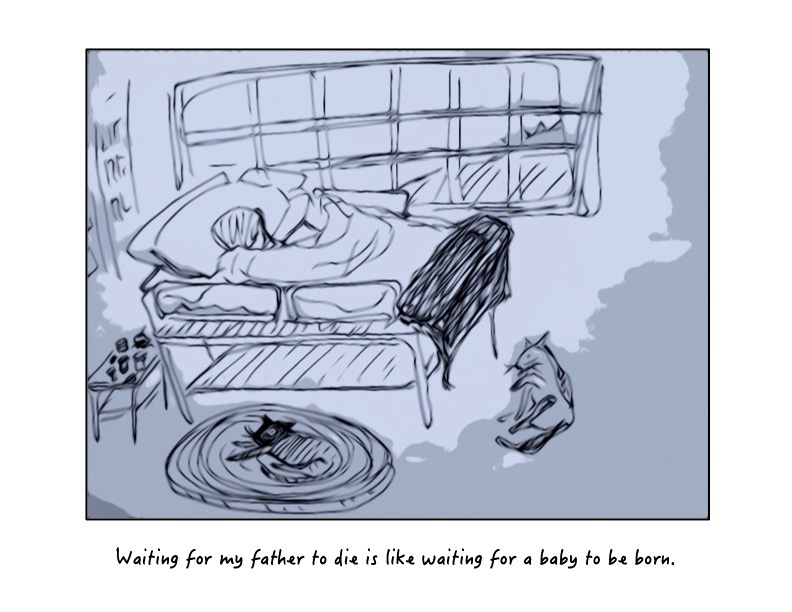

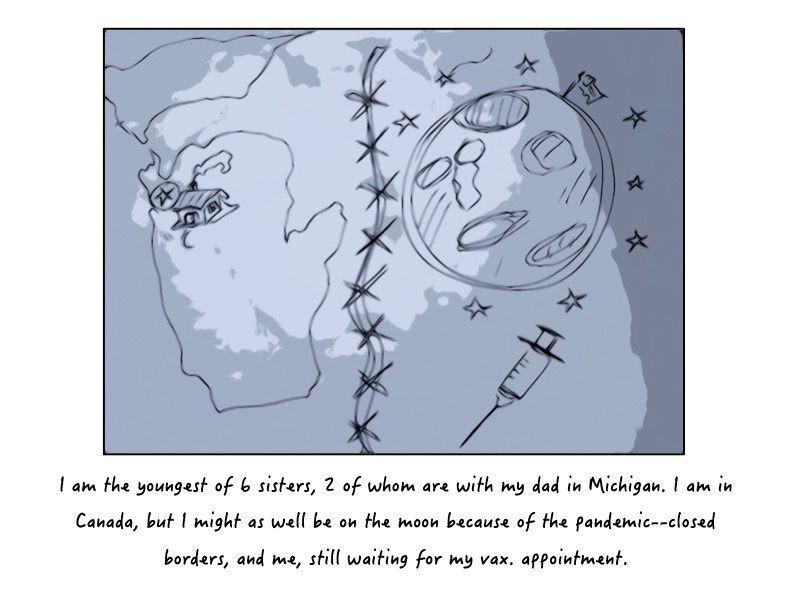

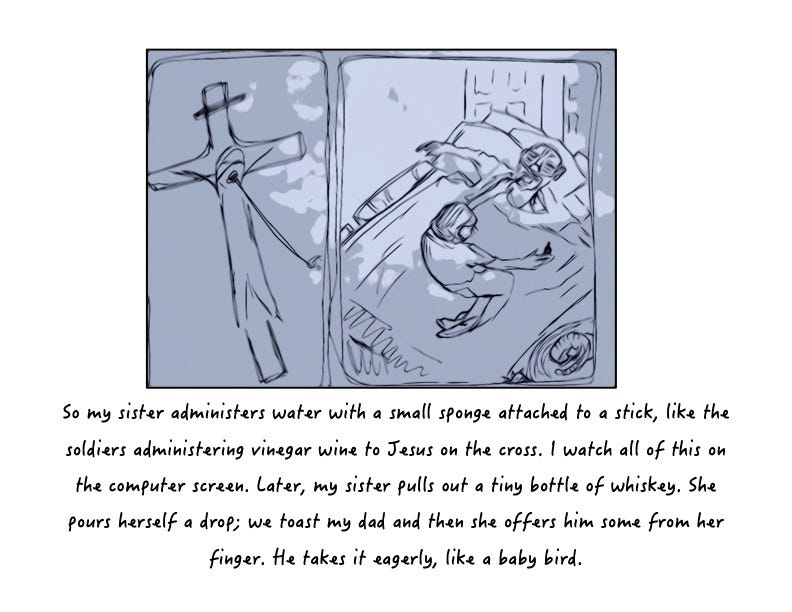

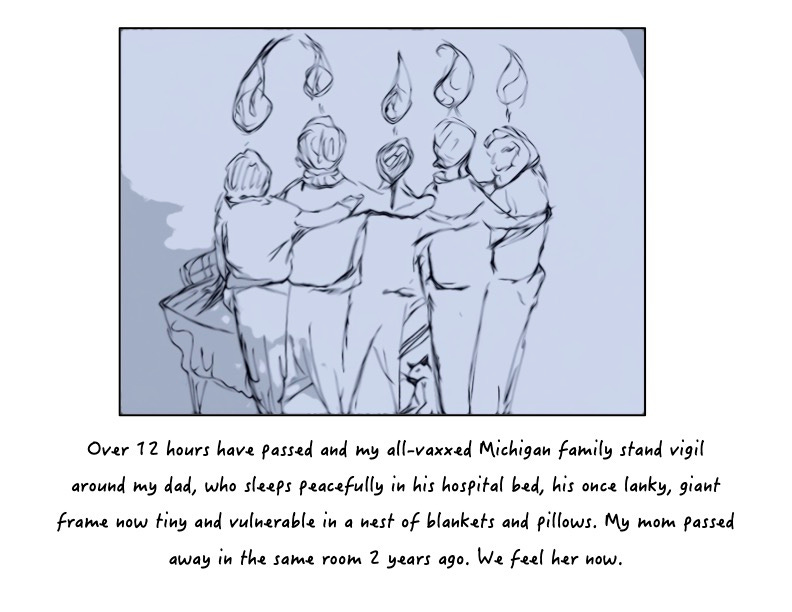

When my dad was on his literal deathbed, nearly four years ago, I sat helpless in my kitchen, several hundreds of miles away.

This was the heart of the pandemic, and in light of all of the variables—he was in the hospital with weakend immunity; I was not yet vaccinated and had small children to care for—with all this in mind and a heavy heart, I decided to stay put.

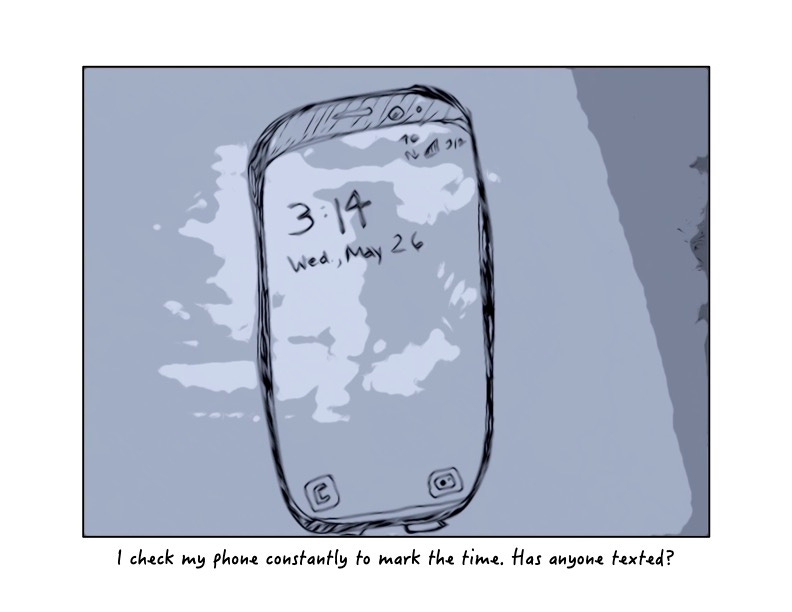

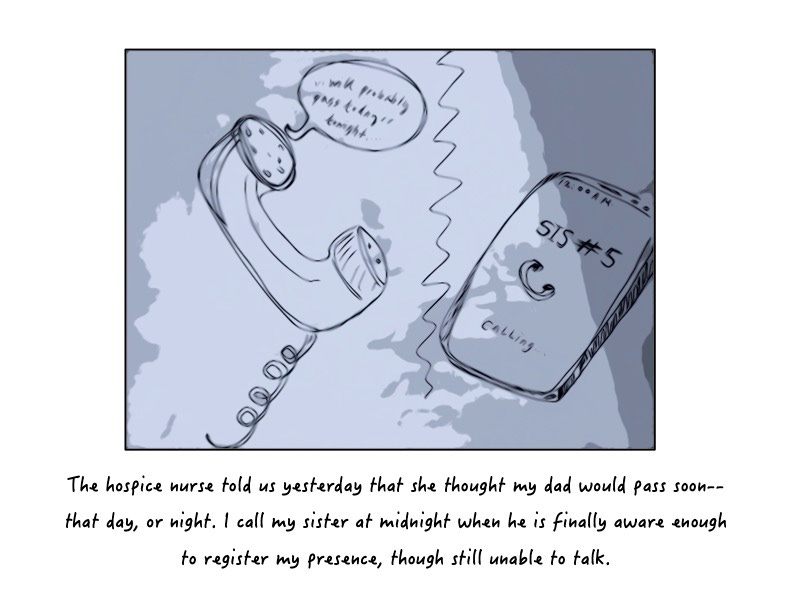

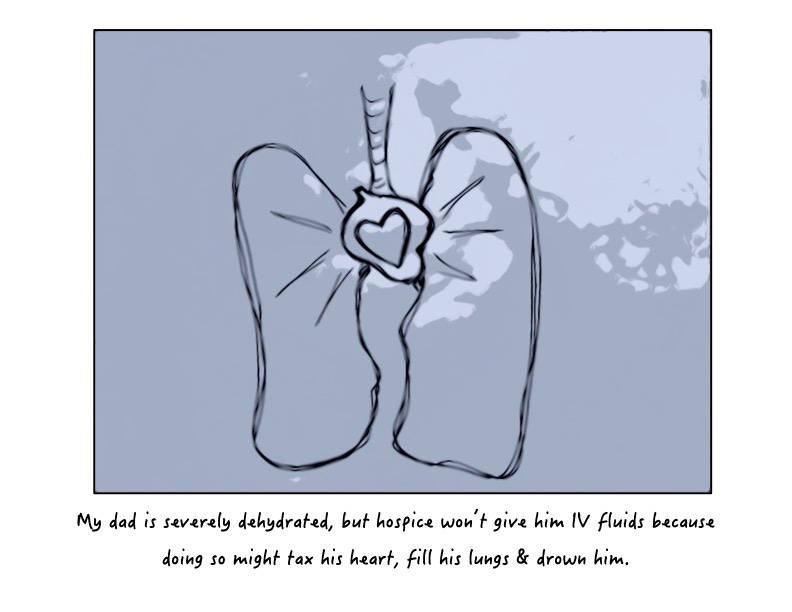

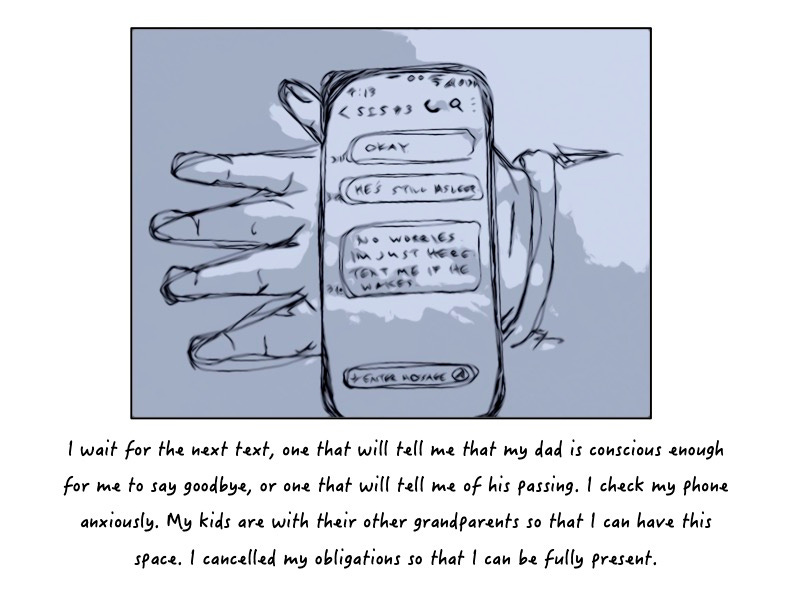

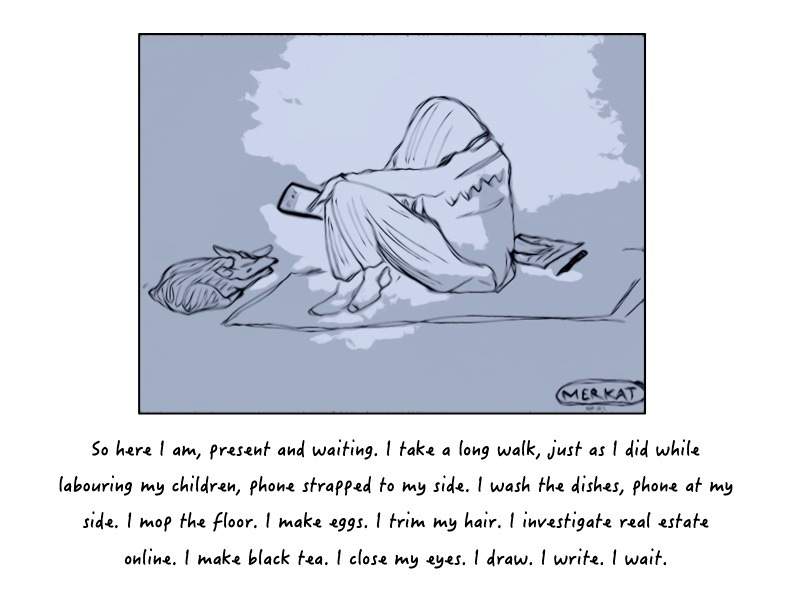

In the last two days of his life, news of his impeding death came to us through the hospice workers. All I could do was sit, and wait.

I did not want to get stuck in the mud of my own mind. I did not want to spin my wheels on metaphysical glare ice. As with traumatic events like the car accident, I felt life slowing down.

Soon I was thinking and feeling in frames.

Frame by frame, I managed my fears.

Frame by frame, I constructed a narrative around my experience, even as I was living it.

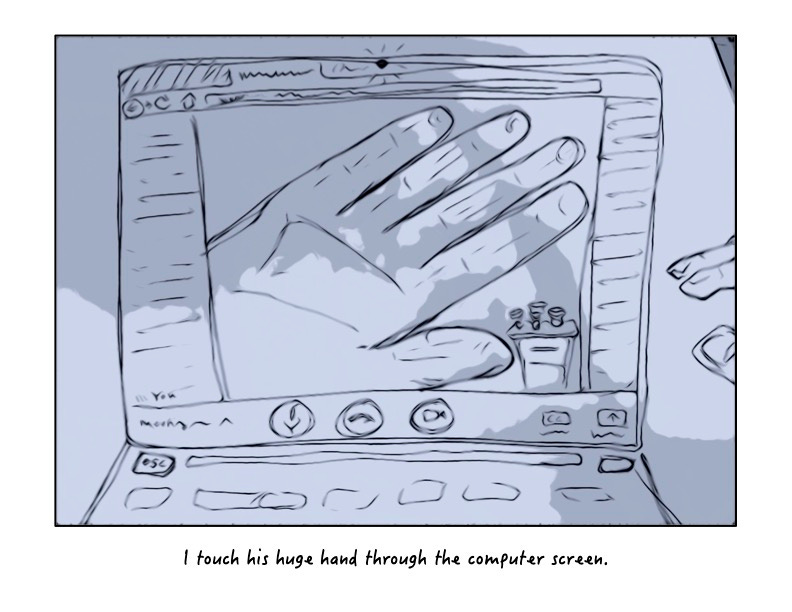

In an effort to make manifest what I was feeling, and to document the experience of my dad’s transition, I made a comic. The very act of making aided in the processing of my grief.

***

Years before, a much younger, fresh-from-university me, poised to teach the next generation of high school students, scoffed at the then-emerging genre of graphic novels (emerging as in, these things have been around in some form since hieroglyphs, but have now hit the contemporary mainstream), dismissing them as somehow suspect.

That was before I encountered PPD and found Powdered Milk. Before I read Burrow. Before I read Funhome and Are you My Mother? and Rx and so many other graphic novels that completely dismantled my outworn prejudices about what makes good literature.

Frame by frame, these works—perhaps, I daresay, more than any novel has ever done for me—spoke to my life with such relatable force, such attention to emotional nuance, that in my most isolated, stuck-in-the-emotional-snowbank states, I felt seen.

The personal accounts offered up in these graphic novels reframed my own experiences as not singular, but shared. Not uncommon; instead, unbelievably, witheringly, sacredly common.

***

Breaking big moments into frames—as Powdered Milk and Burrow do for the postpartum period, or as Funhome and Are You My Mother do for unpacking family of origin dynamics—parsing these big experiences down into smaller, measurable moments is, in itself, a kind of narrative magic.

Working frame by frame, mental health, relationship issues—even grief and death itself—are slowed down in order that the reader may process the narrative at a manageable, human-scale pace.

Frame by frame, this genre offers us what so many well-meaning saccharine clichés do not: inherent to the architecture of a graphic novel are the tools with which we readers may learn to dismantle the pains and joys of our own lives, in real time.

This narrative form teaches us to approach the big things (feelings, traumas, changes) of life not in one fell swoop, but rather, frame by [slow, thoughtful, detailed, ordered, intentional] frame.

***

As an amateur driver, switching from two to four-wheel drive allowed me to grasp early on the distinct power of approaching a problem with the proper tools. Of trying a different approach.

Without that concrete experience, I might still be turning inward, chastising myself for some perceived lack rather than looking outward, with soft eyes and curiosity, upon the varigated nature of my circumstances.

Now I notice [literal and metaphorical] bald tires whenever they present themselves, and I’m grateful for the power of recognition that is the lovechild of trial and error.

***

For me at least, slowing down, taking each moment/feeling/relationship/experience frame by frame; imbuing each frame with the capacity to hold multiple ideas and feelings at the same time, feelings about death and life and humour and absurdity—this is how I find peace.

In a world jockeying for our scant attention, slowing down is also one [seemingly] radical way to help create and foster peace within and without.

Frame by frame: this is how we truly meet one another, fully and without judgment.

This is how we find ourselves, over and again: one frame at a time.

FODDER

If you love the Great Lakes and want to help protect them from the [evil] empire, take a gander at this newsletter from

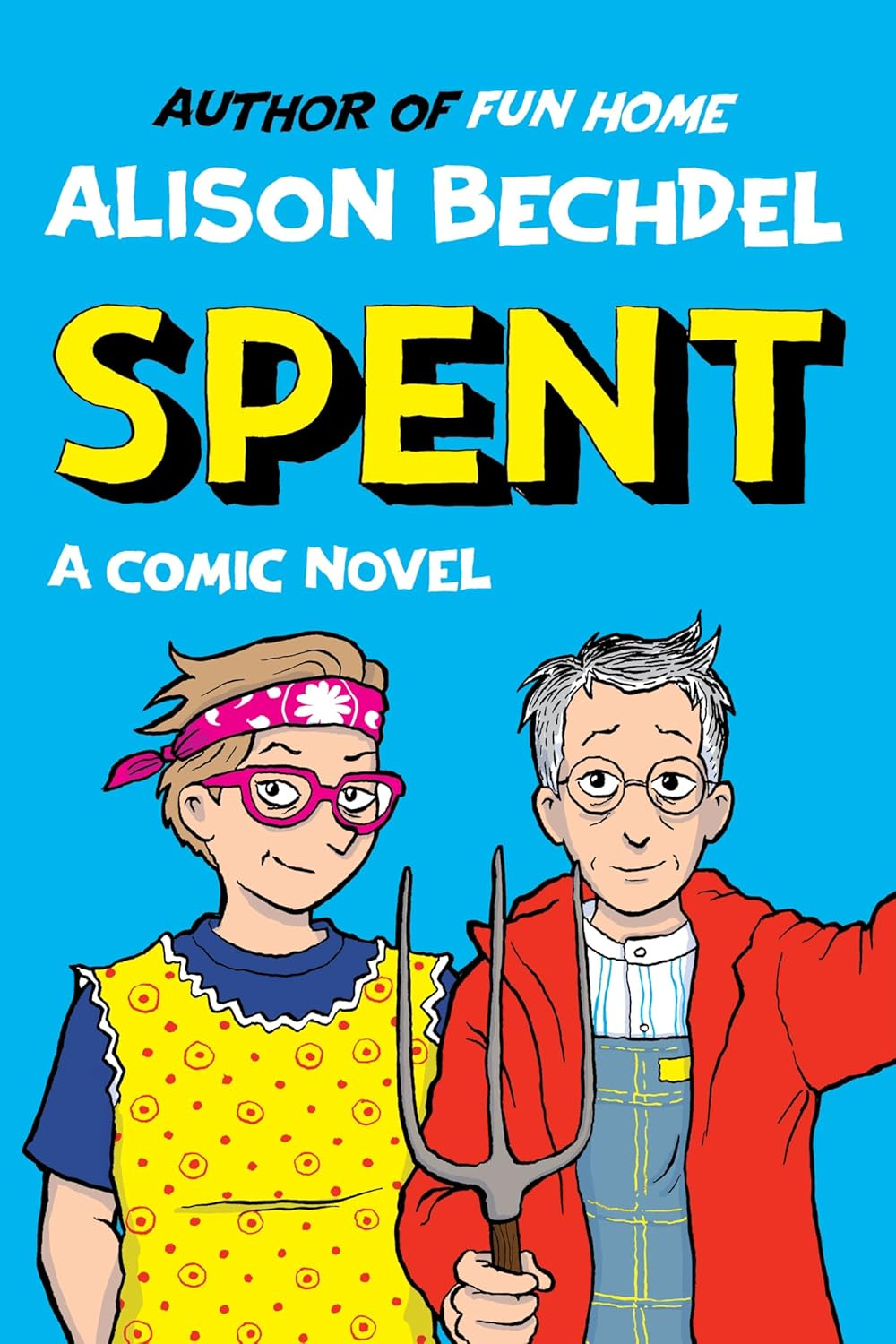

!Speaking of graphic novels, I pre-ordered this book from Reader’s Nook, and it came in this week. Excited to read Alison Bechdel’s new book, Spent!

MY ART/POETRY/EVENTS

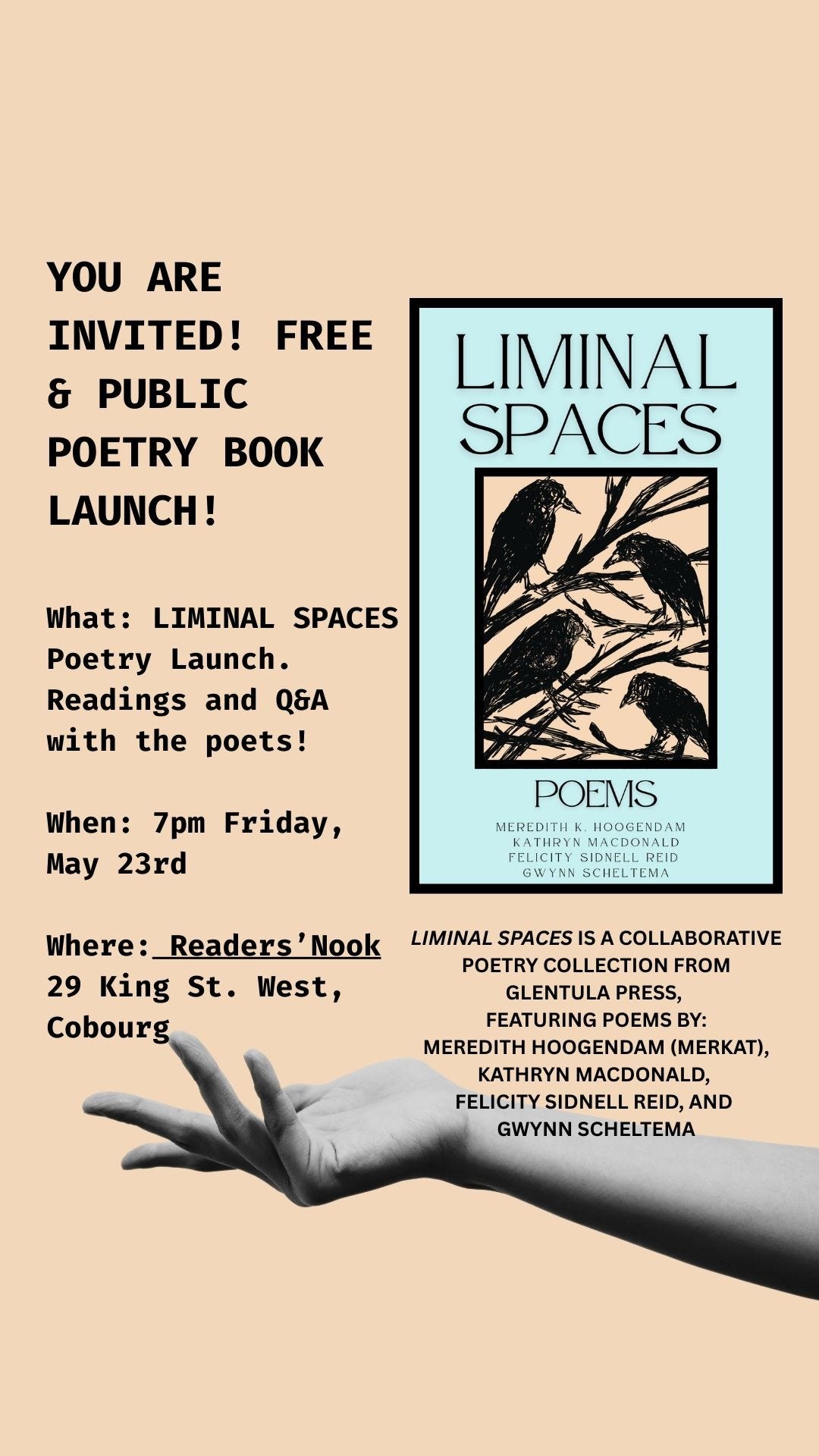

THIS FRIDAY, FREE AND PUBLIC!

FREE COOKIES & savoury treats!

Accompanied by the launch of Liminal Spaces, a collaborative poetry collection filled to the brim with new and never-before-heard poems by Northumberland County poets Felicity Sidnell Reid, Gwynn Scheltema, Kathryn MacDonald, and me!

The launch is free and open to the public, and we'd love to fill Reader's Nook-- the best little independent bookstore in Cobourg--to the rafters with folks ready (or just modestly willing) to enjoy some poetry and Q&A time with the poets (alongside the aforementioned free cookies).

If you can, please join us!

And if you can't make it, but want to support poetry, indie bookstores, and [non-AI] human-made arts, please do spread the word and share the invite to anyone who may be interested. And thanks!

As always, with gratitude,

MERKAT

"We can wake up, do the things, think the thoughts, and still make it to the end of the day whole. Loved, even. Sometimes, even happy, or joyful, possibly warmly contented. We are not broken."

This brought me to tears. <3